Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

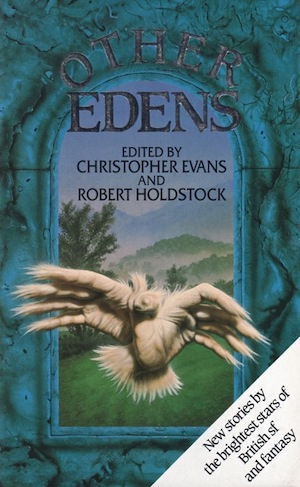

This week, we’re reading Garry Kilworth’s “Hogfoot Right and Bird-Hands,” first published in 1987 in Christopher Evans and Robert Holdstock’s Other Edens anthology. Spoilers ahead; CW for amputation and mention of suicide.

“It would perch on the back of the bed-chair and flutter its fingerfeathers with more dignity than a fantailed dove, and though it remained aloof from the other creatures in the room it would often sit and watch their games from a suitable place above their heads.”

High above the empty streets lives an old woman whose cat has recently died. These days cats are rare, and the old woman can’t afford a new one. So she calls on the welfare machine whose duty it is to look after the lost and lonely.

The machine suggests she fashion a pet from part of her own body. It can remove, say, a foot and modify it to resemble a piglet. Now, the old woman lives in a bed-chair that sees to all her physical needs, not that she suffers any illness beyond apathy and idleness. She spends grey days sleeping, eating and watching her wallscreen play out the lives of people long dead. The bed-chair and her other appliances connect directly to her brain. Seeing no need for her feet, she agrees to the machine’s suggestion.

The old woman at first takes delight in the way Hogfoot Right scuttles around and noses into corners. But unlike her cat, the foot-pig doesn’t like being stroked or fussed over, and the woman tires of its standoffishness. She has the welfare machine fashion her left foot into another piglet, which she names Basil. Basil proves a sweet creature amenable to any amount of fondling. Hogfoot Right, still surly where the woman’s concerned, is generally a good “brother” to Basil, snuggling and even playing with him. In the midst of a sporting tussle, however, Hogfoot Right often takes unaccountable offense and sidles back to a corner, glowering. The old woman eventually gives up on him.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

Encouraged by Basil, she has the welfare machine remove her hands and ears. The ears it makes into a moth. Moth-ears mostly hangs from the woman’s collar, her wings furled, as if longing to return to her former duties. She’s nervous, starting at loud noises, but the woman recognizes an aspect of her own personality and remains happy to keep her.

The hands become a beautiful avian creature–the most delightful pet the old woman’s ever had. Bird-hands flys gracefully around the room, or perches aloof on the windowsill to watch house martins swoop through the sky, or settles on the bed-chair to stroke the woman with her fingerwings. She can play the woman’s disused keyboard instrument or air-dance to its automatic tunes. At night she nestles in the old woman’s lap, and dearly loved.

All live in harmony (even the latest addition, Snake-arm), except the enduringly unsociable Hogfoot Right. The old woman can’t thank her welfare machine enough. She’s very happy, until the night it all goes wrong.

The sound of struggling bodies and crashing furniture wakes the woman. Has a rogue android invaded the apartment? Too afraid even to command a light, she maneuvers her bed-chair into a corner and waits out the ruckus. When silence returns, she orders illumination and gapes at a scene of destruction. Moth-ears lies crushed and torn. A splinter from a shattered lamp has impaled Snake-arm through the head. Basil is black with bruises, fatally beaten.

In the center of the floor, Hogfoot Right and Bird-hands face off. So Hogfoot is the culprit, Bird-hands the woman’s last defender! The pets battle viciously, scattering furniture, rolling about so the woman’s forced to move her bed-chair from their furious path. At last Bird-hands flings Hogfoot Right onto the exposed live contacts of the toppled lamp, electrocuting him!

“Well done,” the woman cries. But Bird-hands begins to fling herself against the window glass, seemingly desperate to join the house martins outside. Then the old woman realizes it was Bird-hands, not Hogfoot Right, who killed the other pets! Poor Hogfoot, misjudged to the end.

Bird-hands flies to the old woman and strokes her throat as if to persuade her to mind-command open the window, as only the woman can. But the woman is as stubborn as Hogfoot Right and refuses to comply. Bird-hands’ caresses turn to slow but inexorable throttling. The old woman’s body convulses, then goes slack.

Bird-hands inspects the other pets for signs of life. She inches toward Hogfoot Right, still sprawled over the live wires of the lamp. Suddenly his head jerks, and his jaws clamp on one of her feather-fingers. Sparks fly, and the room falls still.

Later the welfare machine discovers the carnage. It delivers a verdict of suicide on the old woman and her pets. As it turns to leave, one of the pet corpses stirs. Something snaps at the machine’s metal leg, then goes careering through the open door and into the corridor.

What’s Cyclopean: Kilworth uses simple, even sentimental language to show up the difference between how the old lady sees her pets—whether “temperamental” or “delicate” and “sweet”—and how the reader is likely to see them.

The Degenerate Dutch: Emphasis this week on the old trope that eventually humans will be so well-taken-care-of by our robot overlords that we’ll wither into degenerate couch potatoes and thence into slow extinction. “The old woman was not sick, unless apathy and idleness be looked upon as an illness.”

Weirdbuilding: “Hogfoot Right” leans heavily on familiar tropes (see above, and also check your subway tunnels for morlocks) in order to focus on its far-less-familiar core conceit.

Libronomicon: No books, just reruns on the wallscreen.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Extracting aspects of your personality in the form of body parts could certainly be interpreted as an extreme form of dissociation.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I was going to write a whole essay here about body horror and my extreme susceptibility to it and the prose calisthenics required to pull it off without exasperating everyone who’s ever had to deal with an actual disability. However, I’ve been distracted by an extremely minor yet painful eye injury that is pointing up my complete lack of chill about bodies and their vulnerability to change. (Learn from my error and wear goggles while trying to remove dried-out Christmas trees from their stands. Get your corneal abrasions from proper eldritch sources rather than embarrassingly festive ones.)

My fundamental issue here is an overactive imagination that will happily simulate any injury, surgery, or painful shapeshifting process that I read about in excruciating detail. When I actually have an injury or illness, that same imagination is eager to extrapolate to more, longer, and worse. I’m perfectly aware that the answer to “what will I do if my eye never works again” is both irrelevant to the current situation and “I will talk calmly to my visually-impaired friends who can recommend screen-reader apps,” but this doesn’t change the fact that irrational anxiety is the obnoxious secret in every horror writer’s toolbox. Lovecraft’s set was particularly obnoxious, but we’re all fundamentally working off of “But what if I added plot to my nightmares?” (Though based on this week’s reading, his feelings about the importance of cats seem perfectly reasonable.)

My other fundamental issue is a deep awareness of the research on embodied cognition—the fact that bodies, of all sorts, shape the minds that are a part of them. People rather understandably go to considerable lengths to change their bodies in ways that better fit or better shape their minds. Perhaps the most disturbing thing about Kilworth’s old woman is that she isn’t doing anything like this, nor is she one of those people who actively finds any reminder of having a body distressing. She just finds her body unnecessary—even the parts of it that she still actively uses. She’d rather have more body-pets than be able to stroke the ones she’s got, and I’m still shuddering about that choice, even as I suspect she’s been socialized to it. Notably, the “welfare machine” approves and encourages the whole process. One does wonder how the machines feel about humanity’s dwindling population. Impatient, perhaps?

There is in fact a whole terrifyingly-bland end-of-the-species scenario playing out behind the saga of Hogfoot. The streets are empty, cats are rare, and everyone on the wallscreen is “long since dead.” Rogue androids provide a convenient boogeyman to constrain movement. The omniscient narrator judgily glosses the old woman as apathetic and idle, but it’s not clear that there would be anything to do if she tried to change her “grey days” into something more active.

Once I get past my internal loop of body horror simulation and my concern that there may not be any other humans around, the old woman’s auto-cannibalistic menagerie is itself pretty interesting. They seem to be not merely parts of her body but parts of her mind, including the unexpected part that does want to leave her apartment and fly with the still-plentiful house martins, wants it enough to fight everything that holds her bound to same-ness. I like Hogfoot Right, grumpy and standoffish and protective, but I also sympathize with Bird-Hands and rather hope it got away at the end.

Final note: This is our second story about an independently-animate foot. If we can find a third, it’ll be an official subgenre.

Anne’s Commentary

On his author’s website, Garry Kilworth recalls his childhood as an “itinerant service brat,” part of which was spent in Aden (now South Yemen), chasing scorpions and camel spiders. An arachnid in the Solifugae order, the camel “spider” is one of the few beasts that can give scorpions a race for the title of World’s Scariest-Ass Arthropod, and win. Make that Scariest-Ass Looking Arthropod, since scorpions whup the nonvenomous camel spiders stingers-down as far as danger to humans goes.

Speculate if you will what body part might produce a pet Solifugid; I’ll take a pass on that one. My speculation is that an intrepid juvenile bug-hunter might well grow into a writer who’d delight in a Hogfoot Right who skulks in obscure corners, wrongly considered the failed amputation-morph while pretty if ultimately homicidal Bird-hands gets all the love.

The Weird editors Ann and Jeff Vandermeer call “Hogfoot Right and Bird-hands” a “weird science-fiction” tale. There’s no disputing the science-fiction part, if only because the story features artificial intelligences in the form of “welfare machines.” It also features–depends upon–a system for biomanipulation that can transform harvested organic matter into independent life forms. Strongly implied is a future dystopian society. Streets are “empty.” People–presumably many more than Kilworth’s old woman–have become “lost and lonely,” voluntarily confined to psionically-operated bed-chairs in psionically-controlled apartments, with wall-screens as their primary stimulation. Non-machine companionship seems confined to pets, but “real” pets have become scarce and expensive.

The wall-screens endlessly spooling out the lives of long-dead people recall Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, with its wall-screen “families.” The scarcity of biological animals recalls Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, in which nuclear war has decimated most species, making mechanical animals the only “empathy objects” most can afford. The degeneration of humanity through “apathy and idleness,” leading to a deadening reliance on tech, is a common notion–when you get major screen time in a Pixar film, like the meat-couches of WALL-E, you know you’ve made it as a trope. This movie and the two novels explain how the BEFORE-TIME became the NOW and vividly detail the NOW. Kilworth does neither in his short story, and its brevity is not the only factor.

Put a dozen of us at a dozen keyboards with the task of fleshing out the world-build of “Hogfoot Right,” and we’d get a dozen different results. It could be an instructive exercise, but it wasn’t one Kilworth had to undertake. The broad details of his story are science-fictional, but its tone is more folkloric, more fairytale, from the outset: “There lived, high above the empty streets in a tall building, an old woman whose pet cat had recently died.” There was an old woman who lived in a shoe, there once was a poor woodcutter whose wife had recently died, leaving him with two children. Once upon a time, never mind exactly when, I’m going to tell you a story essentially true, a psychologically accurate fable, if you like.

Of course we’d like!

Reading “Hogfoot Right,” my first impression was that this old woman could fill a whole episode of Confessions: Animal Hoarding. As real-life hoarders amass animals until they run out of funds and/or family patience and/or government tolerance, she could keep converting body parts into pets until her welfare machine cut her off or she reached the life-sustaining limits of her bed-chair.

Why do people hoard pets? Is it to gather creatures that depend on them utterly, that will (therefore?) love them unconditionally? A rational and compassionate decision to care for other creatures doesn’t figure in full-blown hoarding, which devolves into animal–and self–neglect. Whatever the specifics, it seeks to fill a void through sheer accumulation. Whatever the circumstances that have isolated her, Kilworth’s old woman cannot fill her void with technology or even another living if nonhuman being, animals having become rare luxuries. She has only herself to work with, and so she begins to disintegrate herself.

She disintegrates herself, supposedly, into nonself creatures, companions. In fact, the amputation-morphs are mere fragments of their mother, mirroring aspects of her personality. Hogfoot Right embodies her stubbornness, her determination; Basil her playful, unguarded and loving impulses, her “child” side. Moth-ears bundles her neuroses, her anxiety and shyness and resistance to change. Snake-arm, with its “sinuous movements,” is some part of her persona, her sensuality perhaps, that can alarm her.

Bird-hands is the most complex amputation-morph. I call it as the woman’s creative capacities, the parts of herself she admires most, and yet which she stifles, perhaps due to long indifference or suppression from her dystopian environment. Bird-hands longs for the freedom of the house martins it observes through the window; thwarted, its drive to create becomes a rage to destroy.

Hogfoot Right, that irrepressible explorer of perimeters, also longs for freedom. If hands enable humans to create, feet enable them to move. Movement implies destination, purpose, will; the willfulness which defines Hogfoot sustains perseverance, without which the impulse to create is hamstrung, no porcine pun intended.

Because Kilworth’s old woman has physically severed foot from hands, they can’t work together. The symbolic separation is between creativity and will. In attacking its own driver, creativity ultimately destroys itself. In disintegrating herself, the woman commits delayed but inevitable suicide, and so the welfare machine’s verdict on her death is accurate.

Hold on, though. The “welfare” machine is what suggested the old woman disintegrate herself. It enabled her to continue the disintegration. It glorified Bird-hands with silk gloves, while rendering Hogfoot Right ridiculous in an old boot, thus widening their fatal separation. What’s the machine up to here? Does it act as a will-less agent of human government, or are the machines now the rulers?

There’s a question to pose to our dozen world-builders. Me, I’d read much into Hogfoot’s survival and the way he snaps at the welfare machine’s leg before careering out of the apartment, free at last.

Next week, we continue our readthrough of The Haunting of Hill House with Chapter 7.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.